Summary

In Part I of this series on the Bethsaida section of the Gospel of Mark, I argued that the role of the blind man of Bethsaida was played by Titus Flavius Clemens. Mark wrote the scene ot honor Clemens. Here, I build on Part I. I discuss the second feeding miracle in the Gospel of Mark. I propose that the second feeding miracle immediately preceded the healing of the blind man of Bethsaida, and the scenes were linked. I propose the chiasm of the original Bethsaida section. In Part III, I discuss the editing of the Bethsaida section.

Assumptions

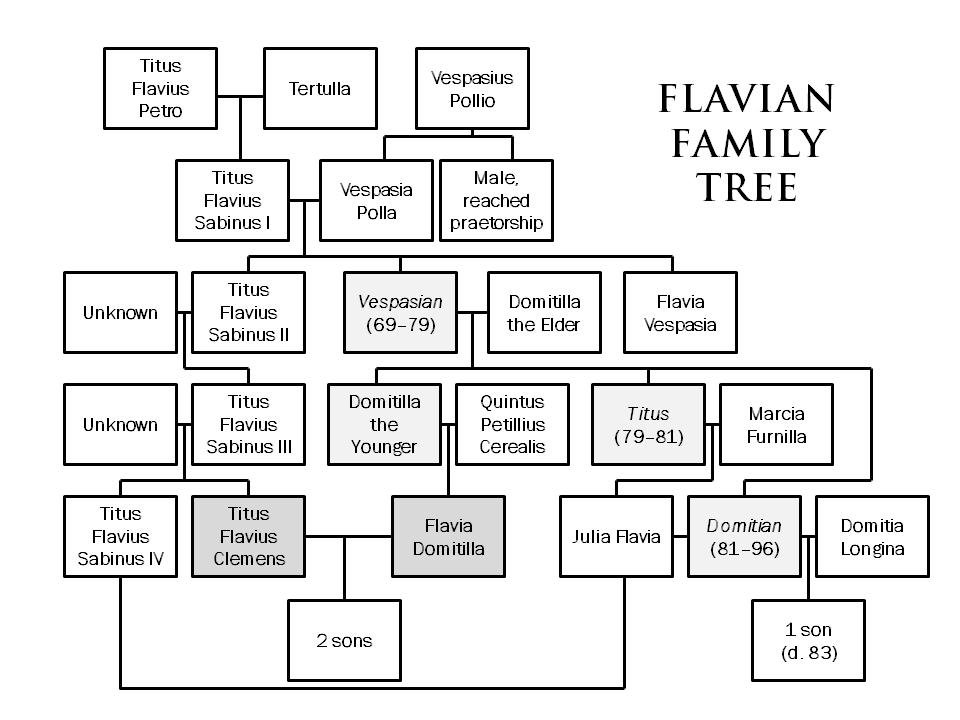

- Titus Flavius Clemens played the role of the blind man of Bethsaida.

- The Gospel of Mark has been edited, and therefore entire scenes, and elements of scenes, might be edited or not original. The sequence of scenes might also be edited.

- The current Bethsaida section of the Gospel of Mark (6:45-8:26) has two boat trips to Bethsaida. (Mk 6:45: “And straightway he constrained his disciples to get into the ship, and to go to the other side before unto Bethsaida.” Mk 8:22: “And he cometh to Bethsaida…”) There are two scenes that take place in Bethsaida. I think that they were originally adjacent and there was only one boat trip to Bethsaida and back.

The second feeding miracle: distribution of gifts

In my book The Two Gospels of Mark: Performance and Text, I explain why I think that only the Second Feeding Miracle (SFM) is by Mark.

When I read the narrative, and try to imagine how the SFM was staged, I find that it cannot be staged as written. Simply, the action takes too much time. But this unstageable action could be hinting at a different kind of “miracle”: namely, a distribution of gifts of food/a snack to the audience. The gifts were provided by the host(s), Titus Flavius Clemens and Flavia Domitilla. (Distribution of gifts to the audience were standard at outdoor theatrical productions. Mark merely wove his into the ‘story’ of the play.)

1 [Nero] gave many entertainments of different kinds: the Juvenales, chariot races in the Circus, stage-plays, and a gladiatorial show. At the first mentioned he had even old men of consular rank and aged matrons take part. For the games in the Circus he assigned places to the knights apart from the rest, and even matched chariots drawn by four camels. 2 At the plays which he gave for the “Eternity of the Empire,” which by his order were called the Ludi Maximi, parts were taken by several men and women of both the orders; a well known Roman knight mounted an elephant and rode down a rope; a Roman play of Afranius, too, was staged, entitled “The Fire,” and the actors were allowed to carry off the furniture of the burning house and keep it. Every day all kinds of presents were thrown to the people; these included a thousand birds of every kind each day, various kinds of food, tickets for grain, clothing, gold, silver, precious stones, pearls, paintings, slaves, beasts of burden, and even trained wild animals; finally, ships, blocks of houses, and farms.

Suetonius, Life of Nero 11

There are two points here. First, Nero required the most distinguished people of the state to participate in the Juvenales (in 59 CE). Recall that Nero’s term as emperor was 25-35 years before Mark’s play; some of his audience had attended these entertainments. And although Vespasian, who succeded Nero after a year of transition, cut back on public extravagance, still, the line of propriety between the senatorial class and the knights on one side, and the people on the other, had been breached.

In this context, Clemens’s participation as an actor in a stage play was unremarkable. Indeed, it might even have been a sign that he was modern and a man of the people, not an aloof aristocrat. (However, he was not risking much, as the performance was private.)

Second, Suetonius mentions that the audience received gifts, and tickets redeemable for gifts. We can assume that the food that was “thrown” to the audience was edible on the spot (e.g., sweet rolls, fruits, nuts). We can also assume that other producers of plays gave gifts to audiences in the same way. So while it is possible that these food distributions occurred before the play or during intermission, it is not at all a stretch to imagine that the distribution of snacks was a sort of mid-time intermission, and also built into the storyline of Mark’s play.

The two original scenes in Bethsaida

Let us assume that the two scenes that take place in Bethsaida, the SFM and the blind man of Bethsaida scene (BMB) were originally adjacent during the single trip to Bethsaida. Which came first?

There is a good reason to think that the SFM preceded the BMB. The audience receives their snack, and naturally, everything stops for a few minutes. Meanwhile, the ‘action’ resumes with a healing, then Clemens exits from the theater. All eyes are on him. He returns to his seat in the front row (See Part I.) The audience continues to nibble during this scene.

I have no reason to think that any other of the existing scenes in the Gospel of Mark were originally set in Bethsaida. I suppose that is possible, but the integration of SFM and BMB seems perfect. The SFM takes the audience’s attention away from the play; the BMB returns it. The SFM provides the audience with a distraction; the BMB gives the audience time to process the distraction. Therefore, I think that Jesus’s trip to Bethsaida consisted solely of these two scenes.

Chiasm of Mark’s original Bethsaida section

Here, from my book, is my proposal for Mark’s original Bethsaida section. Note that it consists entirely of material still present in the Gospel of Mark.

A) In Judean territory, Jesus tells the Pharisees that they abandon God’s commandments and replace them with their human traditions. Jesus tells the multitudes and the disciples that they cannot be defiled by eating. (7:1-15)

B) Jesus and disciples travel in a boat from Judean territory to Bethsaida (in Gentile territory). Possibly, during the trip, Jesus teaches about bread. (scene is currently missing, subsumed into 8:10. It may have included part of 8:14-21)

C) Gentiles are fed with fish and bread (Second Feeding Miracle) / Distribution of gifts to the audience. (8:1-9)

C’) Healing of blind man (a Gentile) in Bethsaida. (8:22-26)

B’) Jesus and disciples travel in a boat from Gentile Bethsaida to Judean territory. During the trip, Jesus walks on water. (6:47-52)

A’) In Judean territory, Pharisees demand a sign from heaven that Jesus is extraordinary. (8:11-12)

In defense of the above proposed chiasm:

- The sequence of scenes omits scenes that on other grounds I believe were not original (discussed in the book).

- The chiasm is consistent with Mark’s use of chiastic structure for the play as a whole.

- It uses a boat scene that is already in the text (the water walk) and another boat scene that is referred to in 8:10.

- Scenes with Pharisees in Galilee frame the trip to Gentile Bethsaida.

- The discussions with Pharisees relate to the adjacent scenes. (A and B relate to eating; B’ and A’ relate to a sign from heaven.)

- It is stageable (the actors’ movements are logical).

- At the end, it places the actors in position to transition to the next scene “on the way” (8:27-Who do men say I am? and the Recognition).

- Again, it consists entirely of material still present in the Gospel of Mark – I did not invent anything.

In Part III I will begin from this point, and discuss how and why Mark’s original Bethsaida section was edited.

version December 24, 2022