Summary

The episode of the cursing of the fig tree in the Gospel of Mark is not good theater. It follows the triumphal entry into Jerusalem, and brackets the Temple Incident (TI). The fig-tree episode should have some relationship to either the triumph or to Jesus’s actions in the Temple. But instead, Jesus explains to the disciples that he is demonstrating that if they have faith, their prayers will be answered. However, there is no immediate reason for him to teach this lesson! And the scene cannot mean that God has ‘withered’ the Judeans in favor of Jesus and his followers, because that is the premise of the play. The fig-tree episode is condensed in the Gospel of Matthew, and omitted in the Gospel of Luke.

I suggest that the two-part episode of the withered fig tree in GMark is an editor’s creation that overwrites Mark’s original scene. The withering of the fig tree, whose leaves are hand-shaped, is an inverted duplication of Jesus’s healing of a man’s withered hand in Mark 3. The original dialogue is replaced by a noncontroversial exhortation to faith.

The fig-tree episode in the received Gospel of Mark

12 On the following day, when they came from Bethany, he was hungry. 13 Seeing in the distance a fig tree in leaf, he went to see whether perhaps he would find anything on it. When he came to it, he found nothing but leaves, for it was not the season for figs. 14 He said to it, “May no one ever eat fruit from you again.” And his disciples heard it. (Mark 11:12-14, NRSV)

[The Temple Incident]

20 In the morning as they passed by, they saw the fig tree withered away to its roots. 21 Then Peter remembered and said to him, “Rabbi, look! The fig tree that you cursed has withered.” 22 Jesus answered them, “Have[b] faith in God. 23 Truly I tell you, if you say to this mountain, ‘Be taken up and thrown into the sea,’ and if you do not doubt in your heart, but believe that what you say will come to pass, it will be done for you. 24 So I tell you, whatever you ask for in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours. 25 “Whenever you stand praying, forgive, if you have anything against anyone; so that your Father in heaven may also forgive you your trespasses.” (Mark 11:20-25, NRSV)

The poor theatrical quality of the episode

I assume that the Gospel of Mark is a narrative of a play written for performance, and performed. Technically, the fig-tree episode (both parts) is feasible in a theater; all that is needed is a prop tree. It should be ‘self-withering’; the dramatic effect of Jesus’s curse is seriously impaired if any of the audience members observe a stagehand swapping a healthy tree for a withered tree. So let us assume a self-withering tree existed.

The episode is poor theater for two reasons. First, it does not connect to the scenes surrounding it. Jesus has entered Jerusalem in triumph, then observed the Temple set-up, then left (went offstage) to Bethany. Now he is on his way back to the Temple, where he will incite the Temple Incident. This transition scene should remind the audience of Jesus’s rationale for his upcoming rampage, or his expectations of the behavior of the Council, or a prediction of his future. But in fact, the two fig-tree scenes are dramatically inert padding.

I note that if the fig-tree episode is original, the dead fig tree remains onstage (actually, in the orchestra) during Mark 12, while Jesus teaches in the Temple. The dead tree remains part of the “around-Jerusalem” landscape. There is no switch in location that requires its removal until the action shifts to Bethany in Mark 14. So in the received text, the dead fig tree remains in the orchestra, useless and unremarked. And the issue of rewarded faith that supposedly motivated Jesus to curse the fig tree, never comes up again.

The fig-tree episode is also poor theater because it not internally consistent dramatically. An ancient reader/listener would have been just as puzzled as a modern reader who takes the scene at face value. First Jesus is hungry. (He’s never been hungry before, and as a semi-divine being he should not need human food.) When he examines a fig tree and finds there are no figs, he punishes the fig tree and the humans who need its fruits. He doesn’t actually tell the fig tree to die; he tells God to make the fig tree never produce fruits again. (God, presumably, decides to do this by withering the fig tree; though God could have done this in another way.) When Peter later notices that the fig tree has withered, Jesus explains that this is a lesson in faith for the disciples; if they have enough faith, they can do anything. But the disciples haven’t asked how they can be more effective; the lesson addresses a question they don’t have. And the reader can justifiably ask why Jesus is suddenly cruel to the fig tree that cannot produce fruit because it is not the season for figs. All of these things don’t cohere into a scene with a single meaning that advances the action of the larger play.

Why were Mark’s original transition scenes–whatever they were–replaced? This is one, admittedly extremely speculative, possible reason. Jesus’s original speech might—might—have had parallels to the speech/behavior of the general Titus Flavius who entered Jerusalem during the Jewish War. (Titus’s niece was in the audience, so a reference to him was possible.) As time went on, such a speech in Mark’s text could become politically questionable.

What the fig tree does not mean

I reviewed other scholarly work on the fig tree in the Gospel of Mark, and discarded some angles of analysis:

- The fig tree does not represent the sacred fig trees of Rome. The audience saw Jesus and disciples enter and leave the Temple in Jerusalem. The audience was thinking only about Jerusalem.

- The fig tree does not represent Judean learning or other sects of Judean religion, or the Judean people as a whole. In the context of the action of the play, these are irrelevant. Jesus has just entered Jerusalem in triumph. He is planning his provocation of the Council of Judea. He is not thinking about how ordinary Judeans perceive him (now or in the future). He has opposed Pharisaic/scribal interpretation of Scripture. The fig-tree scenes must be understood within the lines of action of a performed play. Mark is telling a story about a son of God/divine man who came to earth on a mission to die and rise. The entire premise of the story is that Jesus is the way forward for the Judean people! A didactic metaphor is superfluous.

- Jesus’s explanation of his curse to his disciples makes no sense. According to the received text, Jesus is giving the disciples a lesson in the rewards of faith. If that were indeed his goal, he could have made the fig tree bloom, or produce desirable figs. It is out of character for Jesus to malevolently destroy a food tree.

The withered hand and the withered fig tree

Here I will propose that an editor overwrote Mark’s original transition scenes that surrounded the Temple Incident.

In Strong’s Greek we can see that the same Greek root is used:

ἐξηραμμένην (exērammenēn) — 2 Occurrences

Mark 3:1V-RPM/P-AFS

GRK: ἐκεῖ ἄνθρωπος ἐξηραμμένην ἔχων τὴν

NAS: was there whose hand was withered.

KJV: there which had a withered hand.

INT: there a man withered having the

Mark 11:20V-RPM/P-AFS

GRK: τὴν συκῆν ἐξηραμμένην ἐκ ῥιζῶν

NAS: the fig tree withered from the roots

KJV: the fig tree dried up from

INT: the fig tree dried up from [the] roots

ἐξήρανται (exērantai) — 1 Occurrence

Mark 11:21 V-RIM/P-3S

GRK: ἣν κατηράσω ἐξήρανται

NAS: which You cursed has withered.

KJV: which thou cursedst is withered away.

INT: which you cursed is dried up

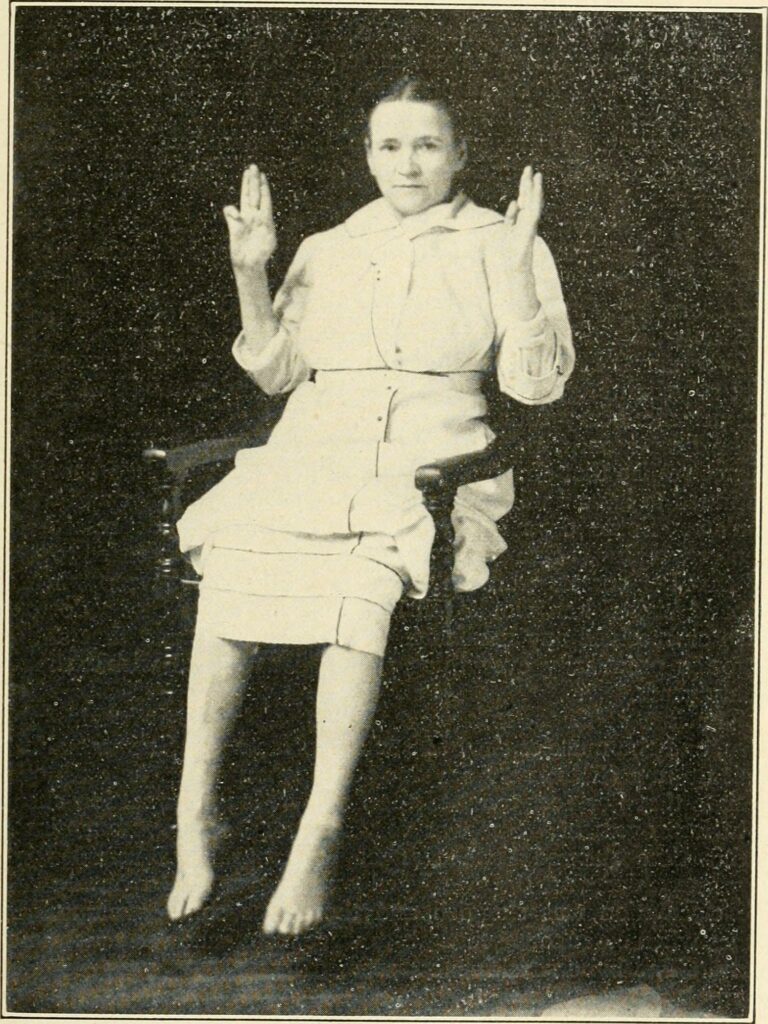

In Mark 3, the term “withered” was a narrative description in Mark’s text; the word was not spoken onstage. In the performed play, the audience saw a spastic or paralyzed hand that became limber (see image below). The concept of “withered” was only one of several ways the audience could have understood the man’s affliction, if they even bothered to put their experience into words.

In the second fig-tree scene, Peter does speak the word “withered” in dialogue, “The fig tree that you cursed has withered” (11:21). Assuming that this scene was performed, the audience at the performance was unlikely to think that this scene referred to Mark 3:1.

Now imagine an editor of Mark’s narrative text. The editor is dissatisfied with Mark’s versions of Mark 11:12-14 and 11:20-25. The editor reads in 3:1 that Jesus had healed a man with a “withered hand.” The editor, conservatively, does not want to change Mark’s text. So the editor has Jesus perform a second miracle, this time on a tree with hand-like leaves. (See image below of the leaves of the edible fig tree, Ficus carica.) But this time, Jesus causes the ‘hands’ to wither. The curse that withers the tree is the inverse of the healing that had earlier restored the withered hand. I further suggest that the editor told the reader that something was amiss with dialogue about the rewards of faith, a subject that is irrelevant within the play.

I note that such duplication is plausible, because the Gospel of Mark contains a duplicate scene. The first feeding miracle is an (editor’s) duplicate of the (original) second feeding miracle. (I discuss this in the book.) Possibly the same editor made both duplications.

The marginal gloss in Mark 11:25 makes the entire speech suspicious

Michael Turton comments on 11:25 “This is the only time ‘your father in the heavens’ occurs in Mark. Though it is attested in all manuscripts, it is mostly likely a marginal gloss that found its way into the text, since the language is Matthean rather than Markan (Ludemann, Gerd. 2001. Jesus After 2000 Years: What He Really Did And Said. Amherst, NY: Prometheus, p79).” I say that this marginal gloss makes 11:22-25 suspicious, because Jesus’s exhortation on faith in those verses is pastoral and out of place in the action of the play.

The fig-tree episode is changed in GMatthew and omitted in GLuke

Matthew condenses the fig-tree episode into one scene (Mt 21:18-22). Obviously, Matthew did not see any value in having the curse and its fulfillment separated in time. I suggest that Matthew’s condensation was more efficient; there is no dramatic reason for Mark to have separated the curse from its fulfillment. Why then do two scenes exist? I can only suggest that in the play Mark wrote two transition scenes that bracketed the Temple Incident; in these two scenes, Jesus spoke with the disciples about the Temple/Temple Incident/consequences of the Temple Incident. An editor of GMark rewrote these two scenes.

Luke may have disliked the fig-tree episode in GMark for religious reasons: “On the whole, from the perspective of Luke the Marcan fig tree story was easily seen either to be at odds with the Lucan characterization of Jesus (if it portrayed Jesus as callously indifferent to the tree) or, more likely, with Lucan eschatology (if it taught the complete end of God’s dealings with Israel). Consequently, Luke omitted it. Kinman, Brent. “Lucan Eschatology and the Missing Fig Tree.” Journal of Biblical Literature 113, no. 4 (1994): 678. doi:10.2307/3266713. But it is interesting that Luke was willing to jettison the exhortation to faith spoken by (the Markan editor’s) Jesus. I infer that Luke felt that the exhortation was not that important; the same concept could be moved elsewhere in GLuke. Luke’s lack of respect for what apparently original Markan material with an uncontroversial doctrinal point also suggests that the fig-tree episode in GMark was not original.