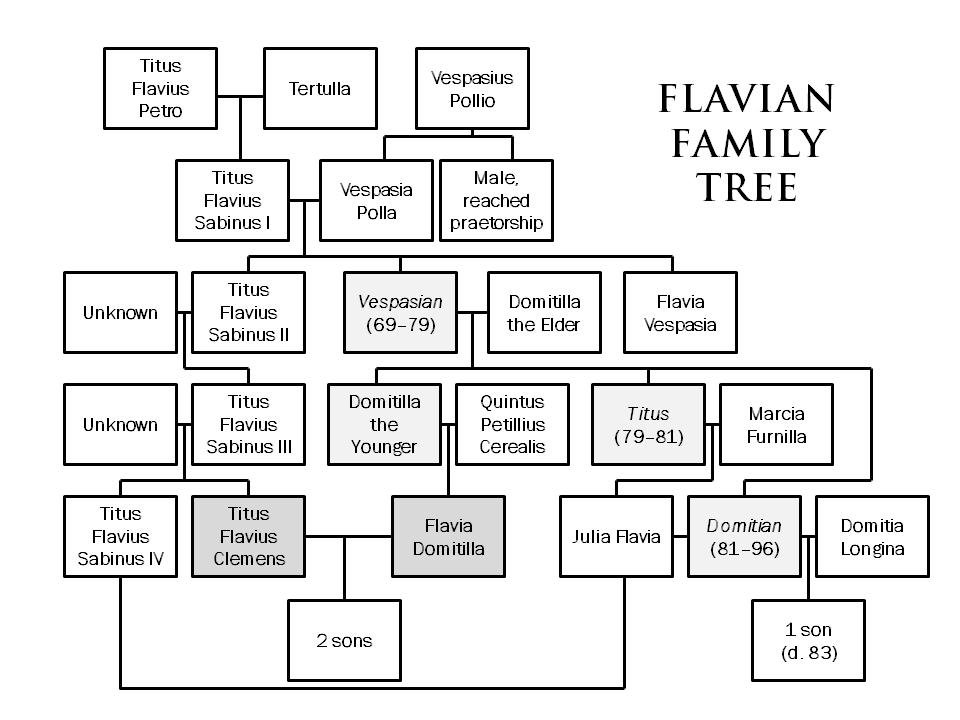

In an earlier post, I identified the Judean princess Berenice as the original of Saint Veronica. In orthodox tradition, early on “Veronica” was identified with Rome. (In actuality, that meant she was identified with the congregation of proto-Christians in Rome that included Mark, Flavia Domitilla, and later the popes.) I etymologically connected “Veronica” with “Berenice.” Berenice was a Herodian princess who lived in Rome in the late first century.

Berenice remained a client of the Flavian family after the death of her patron, the emperor Titus. We can assume that she remained in Rome. There, she was perfectly positioned to be a mother figure/mentor to the orphaned Flavia. (Flavia’s mother had died when the girl was under 10 years old; her father was a general who was always away.) Berenice was some 25 years older than Flavia, and had had two sons in her youth. Flavia had no close older female relatives.

In this post, I present a historical fact that strengthens my suggestion that Berenice was a mentor to Flavia. Namely, that a gravestone of Tatia Baucyl, nutrix, tells us that Flavia had seven children.

An orphan, Flavia must have needed parenting advice. Even if the children were largely raised by nurses and tutors, Flavia still needed advice on how to behave as an aristocrat and mother of emperors, and how to prepare her children for their lives as aristocrats (and for the oldest two boys, as emperors). Berenice was a mother and a princess who had assisted her brother in the administration of Judea. Now she was in exile. Like Flavia, she lived in or near court. Her role as a princess was obsolete and there was no popular movement to reinstate her. Berenice had the time and knowledge to mentor Flavia.

Flavia Domitilla’s biography

Suetonius’s Life of Domitian is our main source for the life of Flavia Domitilla, granddaughter of the emperor Vespasian and niece of the emperors Titus and Domitian. Suetonius states that Flavia Domitilla had two sons whom Domitian designated as his successors. The casual reader infers that Flavia had only these two children.

But in fact, Suetonius is writing about emperors. He is only interested in the important children (designated as successors). He had no reason to mention any other children, especially if they all died before having issue, and therefore were irrelevant to the politics of the Roman state. So we can’t infer from Suetonius that Flavia had only two children. And there is a plaque that says she had seven.

Note for French-readers

If anyone wants to read a comprehensive biography of Flavia Domitilla—minus her religious life, which he wisely refuses to speculate about—see Jean Eracle, “Une grande dame de l’ancienne Rome : Flavia Domitilla, petite fille de Vespasien” Echos de Saint-Maurice, 1964, tome 62, p. 109-134. Eracle takes account of the Catholic, textual and archeological sources. He discusses the memorial plaque that states that Flavia Domitilla had seven children. The following discussion uses Eracle’s work.

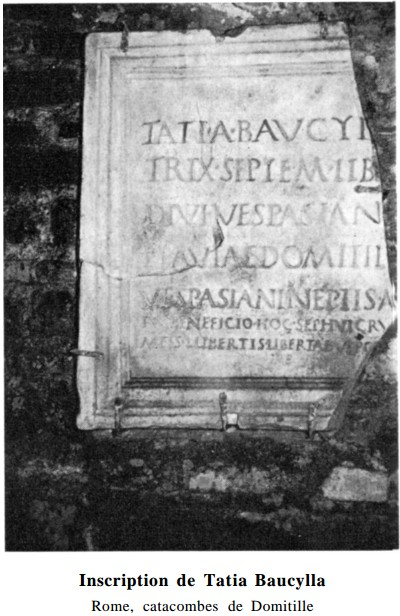

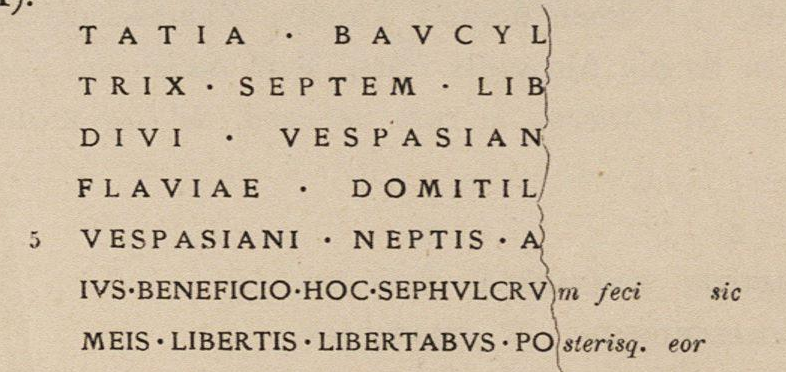

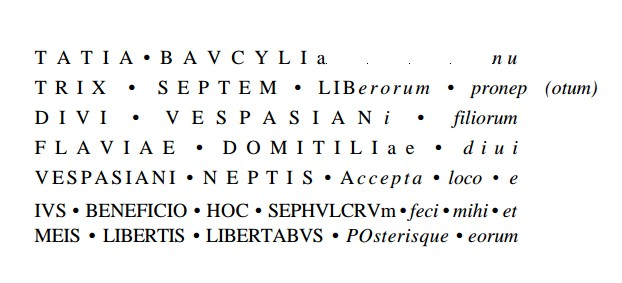

The gravestone of Tatia Baucyl, nutrix

This plaque was found in the cemetery area on the Via Ardeatine in Rome, in the 18th century. The plaque is CIL 6.8942, online at http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/buchseite/952757 :

Eracle writes, p. 115 (my translation): “This inscription, unfortunately damaged, tells us that Tatia Baucylla, (wet-)nurse of seven grandchildren of the divine Vespasian, children of Flavia Domitilla, niece of the divine Vespasian [Domitian], received this plot by the generosity of Domitilla, and here erected a sepulcher for herself, her freedmen, her freedwomen, and their posterity.”

How do we know that this plaque was on Flavia’s property? In the cemetery area on the Via Ardeatine, this plaque is one of two inscriptions that mention “Domitilla.” (Nearby an epitaph of a dwarf, Hector, mentions “Domitilla.”) Eracle writes p. 114 (my translation): “We can therefore be certain that Flavia Domitilla took an active part in the cemetery on her property on the Via Ardeatine.”

Suetonius might be hinting at a large family

Suetonius calls Clemens “a man below contempt for his want of energy” (Life of Domitian 15). This is a strange insult: Clemens’s want of energy was politically prudent. Suetonius knew that Clemens had everything to lose and nothing to gain by participating “energetically,” i.e., conspicuously or assertively, in public life while Domitian was in power. (Domitian could interpet Clemens’s attempts at popularity as a direct threat.)

I speculate that Suetonius’s insult “contemptibly lazy” had a different meaning: it referred to private life, rather than public life. Perhaps Suetonius meant that Clemens (contemptibly) did not practice the Roman virtue of (self-)discipline, i.e. he spent too much time dallying with his wife. Just an idea.

Conclusion

Flavia Domitilla had seven children. She had been orphaned and married off young, and most of the Flavian family were dead. She needed help to navigate the court. Berenice was in the right place at the right time to mentor Flavia in her role as mother of future emperors. I discuss elsewhere that Flavia learned about the Roman congregation through Berenice.

Minor revisions September 20, 2021, October 30, 2021, December 25, 2022